This article was originally published on my Wordpress blog on January 9th, 2014, as an assigment for my Winter Term Media Studies class with the byline: "Alex Anderlik is a senior in the Class of 2014 at Phillips Academy but hails from Missoula, Montana. When he's not wasting time on the Internet, he's trying to figure out how to waste more time on the Internet. You can reach him at google.com/+AlexAnderlik."

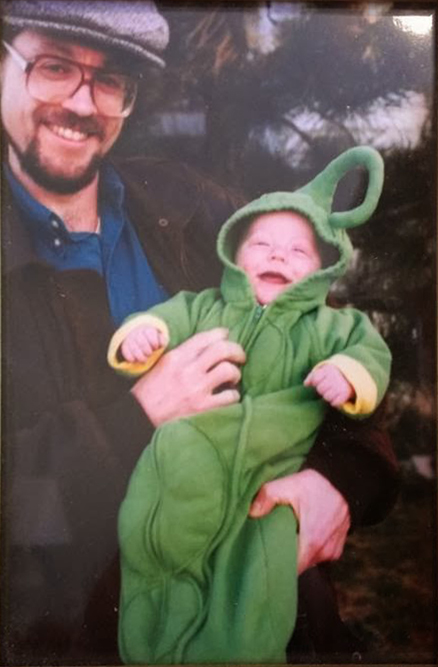

My very first Halloween costume was a pea pod. My mom would repeatedly reminisce about my earliest years and tell me how cute I was. I could always conjure up a vague image of what I looked like based on her descriptions, but obviously I have no real memory of what happened to me; I was an infant. My parents didn’t have many family photos to look at (or at least, none we thought were worth diving into dusty tubs of papers and knick-knacks buried in the basement) and I never actually saw that costume until the summer of 2012 when I found a photograph of it at my grandmother’s house.

My most fashionable look yet.

Susan Sontag’s essay “In Plato’s Cave,” published in 1977 as part of a collection of essays titled On Photography, examines the philosophical and cultural impact photography has had on our society and its perception of reality. Studying Sontag’s theory helps me analyze and reconsider my own opinions and perceptions by giving me a clue as to how I respond to photography and more importantly, why I do. Especially after the introduction of a smartphone into my life, taking snapshots of my world has been such a basic and common part of my habits that until now I was never forced to really think about why I feel so compelled to take and take in photography.

As Sontag confidently claims, “a photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” (p. 5) When I first saw that picture of me as a pea pod, I knew its context instantly and unconsciously decided that yes, there is no longer any doubt that my parents paraded me around as a giant vegetable.

“Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself – a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness,” (p. 8) Sontag explains how these family images often give our brains a jolt of visual details to remind us of otherwise fading memories.However, what Sontag doesn’t elaborate on are the photographs of a time beyond our recall, of the moments which exist in our minds only through the lens of a camera. True, the picture framed in my grandmother’s hallway is proof that my Halloween costume happened, but it’s not just a supplement to my own memory; it’s all that I have left.

One of the questions Sontag alludes to is the tradeoff of the memory in our brains for the “memory” of a photograph. She writes, “A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it – by limiting experience to search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir.” (p. 9) A recent scientific study found that taking photos of something actually causes us to remember fewer details of it than if we were just looking at it. This makes me re-evaluate the definition and importance of my memories themselves… Is it advantage or disadvantage to have a moment captures only in a picture, but not in my mind?

I’d like to think the positive interpretation is the one worth taking. Sontag’s theory on photography presents the medium as a powerful force, both artistic and factual, one that can be shared in large quantities to large numbers of people. Unlike memory, if kept in good condition photographs won’t fade or disappear over time. They give us only a fraction of space and time, but they allow us to interpret and analyze the details of those small parameters in what Sontag and I would probably agree are extremely profound ways.