This article was originally published on Nina Scott's Journalism class website on November 17th, 2013, with the byline: "Alex Anderlik is a senior in the Class of 2014 at Phillips Academy but hails from Missoula, Montana. When he's not wasting time on the Internet, he's trying to figure out how to waste more time on the Internet. You can reach him at google.com/+AlexAnderlik."

Skeletal trees stand between the graves, their fallen leaves forming a crunchy brown and orange carpet over the paths and headstones. The pines around its perimeter creak and groan eerily with the wind. The inscriptions on some of the older tombs have been worn away or obscured by wind, rain, and moss. The graveyard is deserted.

At first glance, this small plot of land might feel more like the setting of a horror film than the resting place of some of Phillips Academy’s most celebrated alumni, faculty, and residents. If you look a bit closer, though, you see the intricacy and diversity of the tombstones whose dates span centuries. Each is as unique and complex as the person buried there.

An unmarked memorial in the shape of an angel.

Unless otherwise stated, the following information comes from a 2006 draft of the Preservation Master Plan for the Chapel Cemetery retrieved from the Phillips Academy Archives.

The Birth of a Burial Ground

The first person buried in the plot of land behind Samuel Phillips Hall was probably a Phillips Academy student named Louis Count Congar. He likely died in the January of 1810, 32 years after the boarding school was founded.

Gail Ralston, Cochran Chapel Office Manager and First Vice President of the Board of the Andover Historical Society, wrote in an email that the first burial was of an Andover student named Lewis LeConte Congar. She said that the procedure was out of necessity because in that era it was often not possible to transport a student’s body home.

The Andover Theological Seminary, which according to the Master Plan was founded across the street from Phillips Academy and used the same board of Trustees, had its own share of bodies in the cemetery.

The History of Andover Theological Seminary by Henry K. Rowe said that if a student from the Seminary died before he finished school, he would be buried in the Chapel Cemetery.

“It has been remarked that there are more brains to the square foot in Chapel Cemetery at Andover than in any similar plot of ground in America,” Rowe wrote.

Ralston said in her email that in total, 19 boys from the Theological Seminary were laid to rest in the cemetery.

According to the Master Plan, on August 16th, 1820, Isaac Blunt sold the land in which Congar was buried to the school for $400. Blunt, a Revolutionary War Captain whose house on the corner of Highland Road and Salem Street was also a tavern, gave the field to the town of Andover which in turn passed it on to the school.

The land continued to be used as a burial site without much organization until several volunteers created the Chapel Cemetery Association, dedicating $25 each to maintain the then-officially-named Chapel Cemetery.

Set in Stone

The Association then fought an uphill battle with the Trustees to secure and improve the cemetery. In 1876, they requested to receive the deed of the land from the Seminary and the Academy. The Trustees denied it for being “inexpedient.”

The monument for Harriet Beecher Stowe with posing students, circa 1928 (courtesy of the Phillips Academy Archives).

In 1884, the Association asked to expand the cemetery, but the Trustees did nothing. A decade later, the same thing happened.

For many years the only notable addition to the cemetery was the grave of Harriet Beecher Stowe, a famous abolitionist who penned the classic anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, when she died in 1898. She lived with her husband and Seminary teacher Calvin in what is now Stowe House, and was also buried next to him.

According to the Abbot Courant of 1898, a granite cross about 12 feet tall was erected over the grave by her children; the Stowe family insisted on building the memorial themselves based on a design of Harriet’s liking, respectfully refusing help even from compassionate former slaves.

The draft of the Master Plan said that in 1905, an attorney named Elias Bishop sought out documentation of meetings, deed ownership, and the names of those buried there. All he discovered was that those records didn’t exist. The Chapel Cemetery Association appeared to be falling apart.

The Association did not get the ownership nor the expanded land they requested until 1908, when they were granted 1.78 acres of land on the condition that the land will be never, ever be used for any purpose but the burial of the dead.

Some gravestones have been worn down by the elements and gained coats of moss.

From that point on through the middle of the 20th century, the Cemetery Association virtually disappeared. The cemetery stayed mostly the same, though it became increasingly crowded with graves, shrubs, and trees.

Rebirth Through Ashes

The Association did not restart until 1972, when the impression that the cemetery was almost full drove interest for expansion. The new Association made more room by turning walkways into burial lots and restricting interment to people who had been Phillips Academy faculty for at least five years.

The Phillips Academy garth.

They also proposed that the northwestern corner of the cemetery contain a garth, a granite ring around a grassy mound 35 feet in diameter which could hold 88 sections of cremated remains.

The garth was designed in 1974 and completed the following year, for a short time alleviating the panic about overcrowding. As a result, it went back to receiving minimal attention.

Students began walking through the cemetery more frequently than ever before. This probably isn’t because they were particularly interested in the graves, but more likely due to the fact that they were living in new dormitories constructed to the north and northeast of the cemetery and were using it as a shortcut.

Because no clear rules had been made regarding student use of the burial grounds, there was worry that graves were being worn down from misuse. The construction of a chain-link fence on the eastern side of the cemetery reduced the number of cemetery visitors to its usual low.

After almost 25 years of hiatus, the Chapel Cemetery Association was revived yet again in 1998, meeting regularly to address concerns of neglect and disorganization. A proposal for funding to build an up-to-date database and long-term plans for care was submitted to the Abbot Academy Association in 2004.

In 2006, assessments of monuments and a survey of the cemetery were completed, and many detailed records can be found on the Find A Grave website.

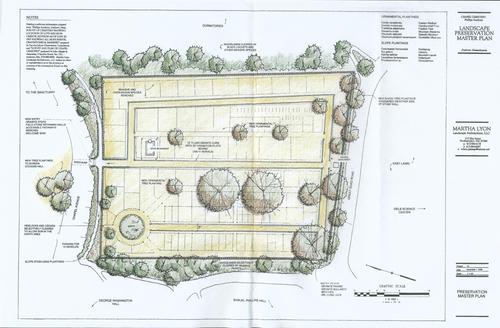

The most recent plan of the cemetery (courtesy of the Phillips Academy Archives).

Living Death

Today, the graveyard remains a hidden gem of the school’s heritage. Ralston, who said she has given campus history tours for many years as part of the Andover Historical Society, researched the cemetery this August and has given three tours – one for faculty, another for the Catholic Student Fellowship, and a third for the general public – in October as part of the Historical Society’s “Bewitched in Andover” series.

She said she gives the tours out of passion for the amount of school history contained in the plot of land barely 2 acres in size.

“It represents early history and those individuals who have created the modern academic program,” she wrote. “It represents innovators, environmentalists and great minds in education. It represents the families who supported them. One way to give it ‘the recognition it deserves’ is for students to be encouraged to uncover its secrets, and, perhaps, for me to give regular cemetery tours!”

In her email, Ralston said that virtually every plot is in use or already owned by a family.

While burials are infrequent they still occur – the most recent burial is of Laura Thompson Hunter, who died this year. The pot of a plant next to her grave was inscribed with a heart and the words “Laura xo.”